Epidemiology and Etiology of Narcolepsy

This content was developed using the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, text revision (ICSD-3-TR) and other materials.

Epidemiology and Etiology of Narcolepsy

This content was developed using the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, text revision (ICSD-3-TR) and other materials.

Overview

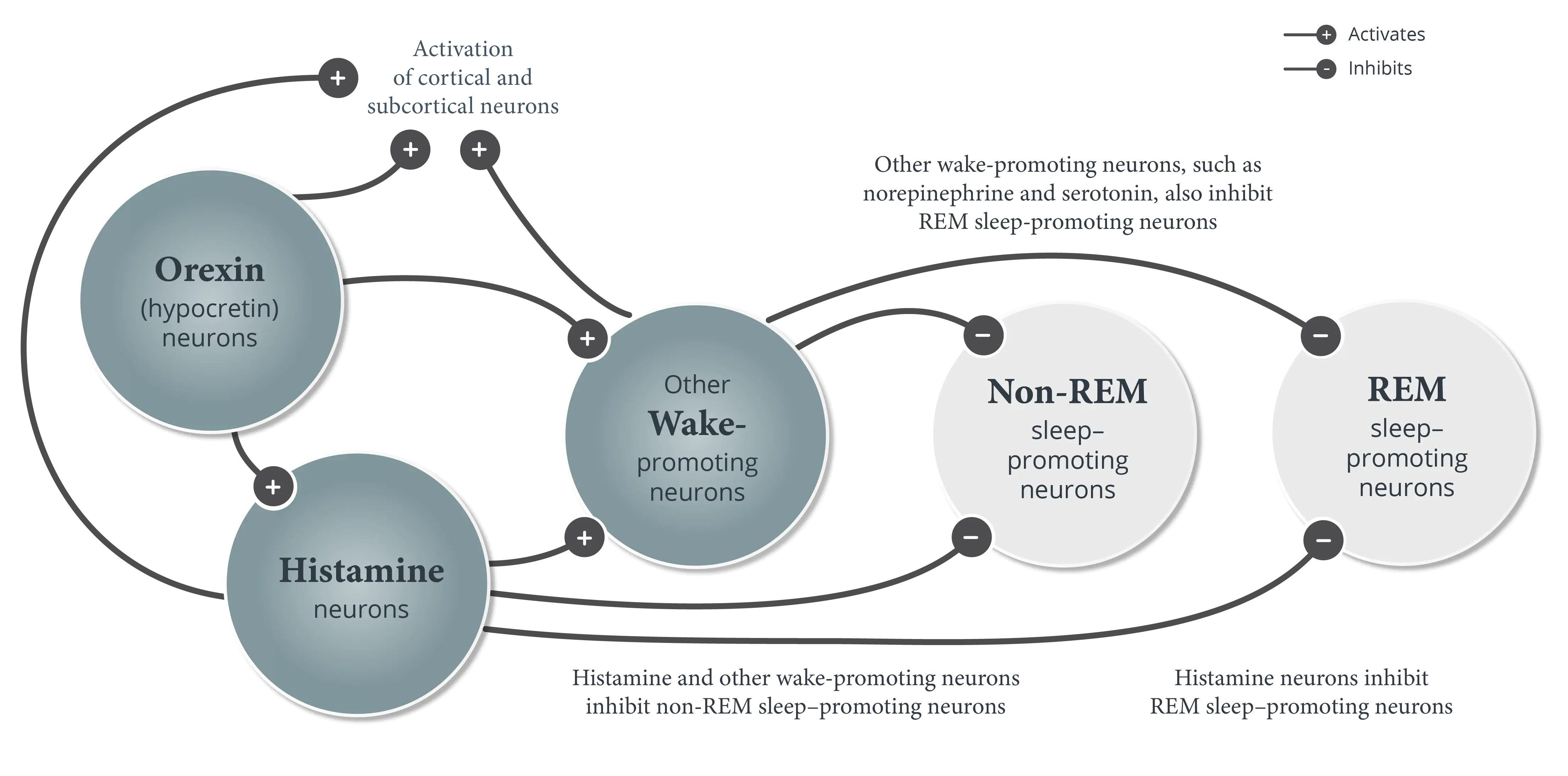

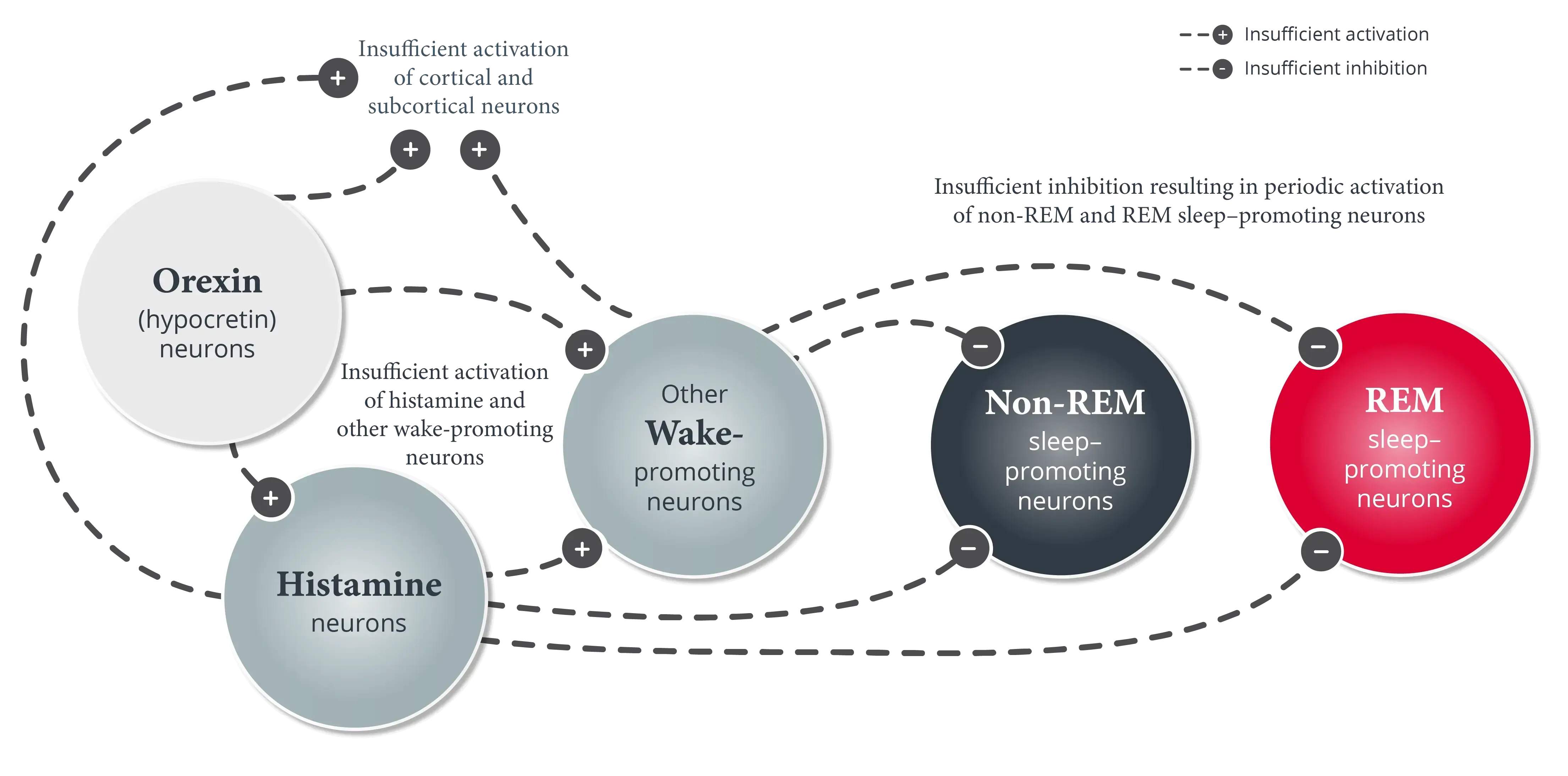

Approximately 170,000 people in the United States have narcolepsy, two-thirds of whom have narcolepsy type 1.1-4 Narcolepsy type 1 is caused by the selective loss of orexin (hypocretin) neurons in the hypothalamus; the cause of narcolepsy type 2 is likely heterogeneous.5,6

Approximately 170,000 people in the United States have narcolepsy, with onset typically occurring between 7 and 25 years of age.1,2,5 Although narcolepsy is rare among the general population, it accounts for approximately 5% of primary diagnoses for adult patients seen in US sleep centers.7,8

Most patients with narcolepsy have undetectable or low (<110 pg/mL) levels of orexin (hypocretin) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).5

Up to two-thirds of patients with narcolepsy have narcolepsy type 1 (also called narcolepsy with cataplexy).3-5 Narcolepsy type 1 is defined by the selective loss of orexin (hypocretin) neurons in the hypothalamus, most likely due to an autoimmune process.1,5,6 The underlying cause of narcolepsy type 2 (also called narcolepsy without cataplexy) is likely heterogeneous and is often not known; however, according to the ICSD-3-TR, approximately 15% to 20% of patients with narcolepsy type 2 have low (≤110 pg/mL) levels of orexin (hypocretin) in the CSF.5

The loss of orexin (hypocretin) neurons is likely triggered by an autoimmune response in genetically predisposed people.1,6 Up to 98% of patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy have the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene variant HLA-DQB1*06:02, compared with 12% to 38% of the general population.5,9

In a study that analyzed blood samples from individuals with narcolepsy, autoreactive CD4+ memory T cells that target self-antigens expressed by orexin (hypocretin) neurons were detected in all participants in the study, regardless of the orexin (hypocretin) deficiency or the presence of HLA subtype DQB1*06:02. Orexin (hypocretin)-specific CD8+ T cells were also detected in some participants in the study.6

Studies have shown an increased rate of narcolepsy onset following seasonal infections like Streptococcus pyogenes, influenza A H1N1 infection, and the H1N1 Pandemrix® vaccine.10-12 To date, only isolated cases of new-onset narcolepsy following COVID-19 infection have been reported, with no definitive conclusion regarding the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism.13,14

The loss of orexin (hypocretin) leads to sleep-wake state instability.15 Learn more about the effect of orexin (hypocretin) loss on other neurons involved in the pathophysiology of narcolepsy.

References

- Scammell TE. Narcolepsy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2654-2662.

- United States Census Bureau. U.S. and World Population Clock. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- Thorpy MJ. Recently approved and upcoming treatments for narcolepsy. CNS Drugs. 2020;34(1):9-27.

- Ruoff C, Rye D. The ICSD-3 and DSM-5 guidelines for diagnosing narcolepsy: clinical relevance and practicality. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(10):1611-1622.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed, text revision. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2023.

- Latorre D, Kallweit U, Armentani E, et al. T cells in patients with narcolepsy target self-antigens of hypocretin neurons. Nature. 2018;562(7725):63-68.

- Punjabi NM, Welch D, Strohl K. Sleep disorders in regional sleep centers: a national cooperative study. Sleep. 2000;23(4):471-480.

- Ahmed I, Thorpy M. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31(2):371-381.

- Partinen M, Kornum BR, Plazzi G, Jennum P, Julkunen I, Vaarala O. Narcolepsy as an autoimmune disease: the role of H1N1 infection and vaccination. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):600-613.

- Han F, Lin L, Warby SC, et al. Narcolepsy onset is seasonal and increased following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in China. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(3):410-417.

- De la Herrán-Arita AK, García-García F. Narcolepsy as an immune-mediated disease. Sleep Disord. 2014;2014:792687. doi:10.1155/2014/792687

- Picchioni D, Hope CR, Harsh JR. A case-control study of the environmental risk factors for narcolepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;29(3-4):185-192.

- Deshpande P, Thomas M, Tran L, Sampath R, Clark DR. A rare case of narcolepsy following SARS-CoV-2 infection (abstract). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:A4589.

- Roya Y, Farzaneh B, Mostafa A-D, Mahsa S, Babak Z. Narcolepsy following COVID-19: a case report and review of potential mechanisms. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11(6):e7370. doi:10.1002/ccr3.7370

- España RA, Scammell TE. Sleep neurobiology from a clinical perspective. Sleep. 2011;34(7):845-858.