Making a Differential Diagnosis for Narcolepsy

This content was developed using “Clinical features and diagnosis of narcolepsy in children,” published on UpToDate (2024), and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, text revision (ICSD-3-TR).

Making a Differential Diagnosis for Narcolepsy

This content was developed using “Clinical features and diagnosis of narcolepsy in children,” published on UpToDate (2024), and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, text revision (ICSD-3-TR).

Overview

A careful clinical history is a key component of making the correct differential diagnosis of narcolepsy.1,2

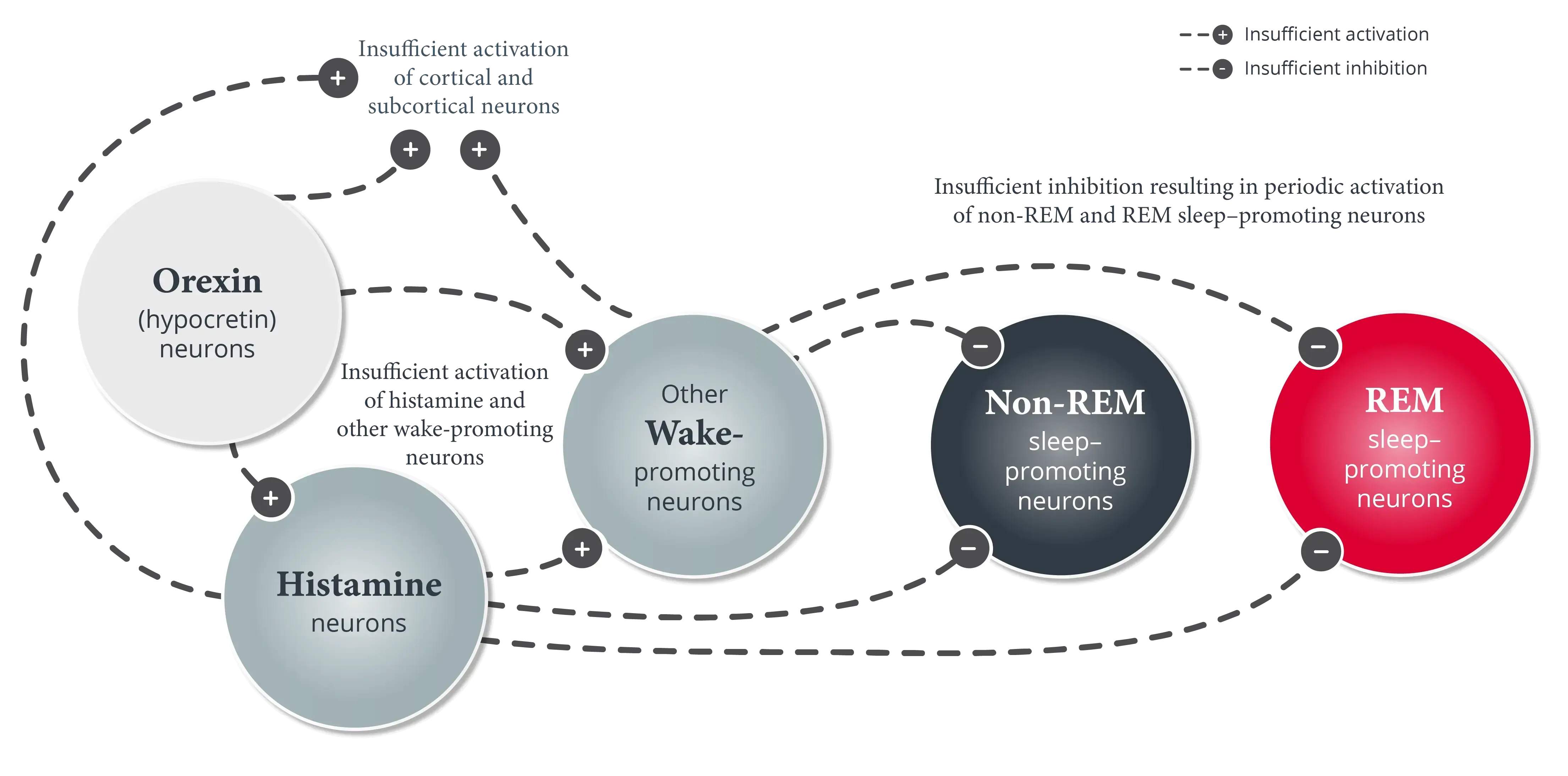

Diagnosis of narcolepsy is based on characteristic clinical features, sleep laboratory testing, and in select patients, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin-1 testing. Narcolepsy diagnosis also requires ruling out other potential causes of daytime sleepiness.1,2

Various alternative diagnoses should be considered when narcolepsy is suspected, especially in the absence of cataplexy. A careful clinical history is therefore a key component of making the correct differential diagnosis.1

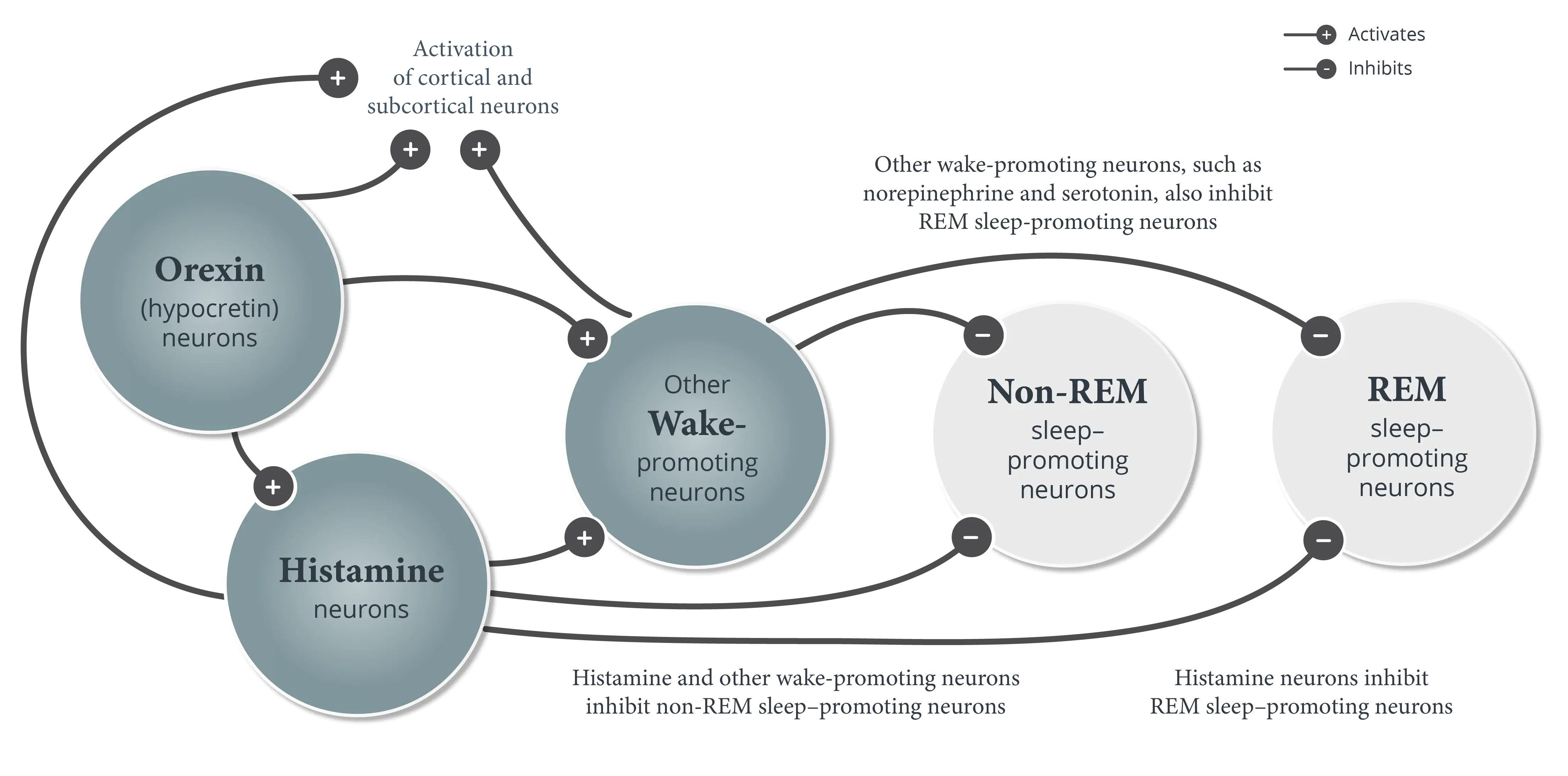

Many conditions can cause excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) by disrupting the duration or quality of nighttime sleep.1 These may include insufficient sleep syndrome, sleep-related breathing disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea [OSA]), periodic limb movement disorder, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders (eg, shift work disorder), other central disorders of hypersomnolence, mood disorders, and use of certain substances or medications.1,2

The possibility of these various conditions causing disruption of sleep underlines the importance of confirming adequate sleep and stable sleep patterns prior to conducting objective testing when narcolepsy is suspected. For example, some conditions may increase the likelihood of sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs) on a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) that may not be specific to a narcolepsy diagnosis.1,2

Genuine cataplexy is highly specific for narcolepsy but may be confused with “pseudocataplexy,” or cataplexy-like attacks that may occur with functional neurological syndrome, as well as cataplexy-like attacks that may sometimes occur in normal individuals (eg, muscle weakness when laughing out loud).1,2 Cataplexy should also be differentiated from other conditions such as syncope, transient ischemic attacks, seizures, and psychological or psychiatric disorders.2

Signs of something other than cataplexy for the diagnosis of narcolepsy type 1 can include loss of consciousness at the start of the attack, >10 minutes of duration in the absence of a precipitating factor, or retention of deep tendon reflexes in limbs affected by the attack. There may also be other clear signs that point away from cataplexy (eg, a typical epileptic “aura,” usual warning signs that occur before vasovagal syncope).2

The detection of genuine cataplexy may be aided by video recordings of attacks with careful attention to facial features during review of these attacks. Hypotonia in the face and weakness in the neck are reliable markers of true cataplexy that occurs in narcolepsy.1 Temporary muscle atonia is also indicative of true cataplexy.1,2

Hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations and sleep paralysis often occur in narcolepsy but may also be reported in patients with insufficient sleep, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, OSA, and anxiety, or with the abrupt withdrawal of REM sleep–suppressing agents (eg, alcohol, amphetamines, antidepressants). Hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations can be differentiated from hallucinations associated with psychotic disorders (eg, schizophrenia) by the association of these symptoms as dreamlike in nature.1

Testing of CSF hypocretin-1 levels is not required for a narcolepsy diagnosis but may be helpful in the following situations1:

- Unreliable MSLT results due to poor nighttime sleep or use of medications that could not be discontinued before testing and may have interfered with or altered the results of the test

- Ruling out narcolepsy in patients presenting only with atypical cataplexy

All patients with narcolepsy have EDS, but not all will exhibit other symptoms of narcolepsy.1,2 A diagnosis of narcolepsy should therefore be considered even in patients with EDS alone. Narcolepsy should immediately be considered in patients with a history of cataplexy.1 As such, conducting an effective clinical interview is critical in making a differential diagnosis.1,2

References

- Scammell TE. Clinical features and diagnosis of narcolepsy in adults. Clinical Decision Support | UpToDate | Wolters Kluwer. Updated December 16, 2024. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-narcolepsy-in-adults

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed, text revision. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2023.